Visualizing the Scale of the Universe with React Three Fiber

Building an interactive 3D journey from the Moon to the Observable Universe, handling 23 orders of magnitude in a web browser.

View Live DemoVisualizing the Scale of the Universe

The universe is incomprehensibly large. I've always been fascinated by those "Powers of Ten" style visualizations that zoom from atoms to galaxies, but most of them are static images or pre-rendered videos. I wanted to build something interactive where you could actually travel through cosmic scale in real-time.

The challenge: how do you render objects that range from the Moon (3.5 million meters) to the Observable Universe (880 septillion meters) in the same 3D scene? That's 23 orders of magnitude. Your typical floating-point precision breaks down long before you get anywhere close to that range.

What It Does

Navigate through 21 celestial objects across four layers of the cosmos:

- Solar System - Moon, planets from Mercury to Jupiter

- Stars - From our Sun to hypergiants like Stephenson 2-18

- Galaxies - Milky Way and Andromeda

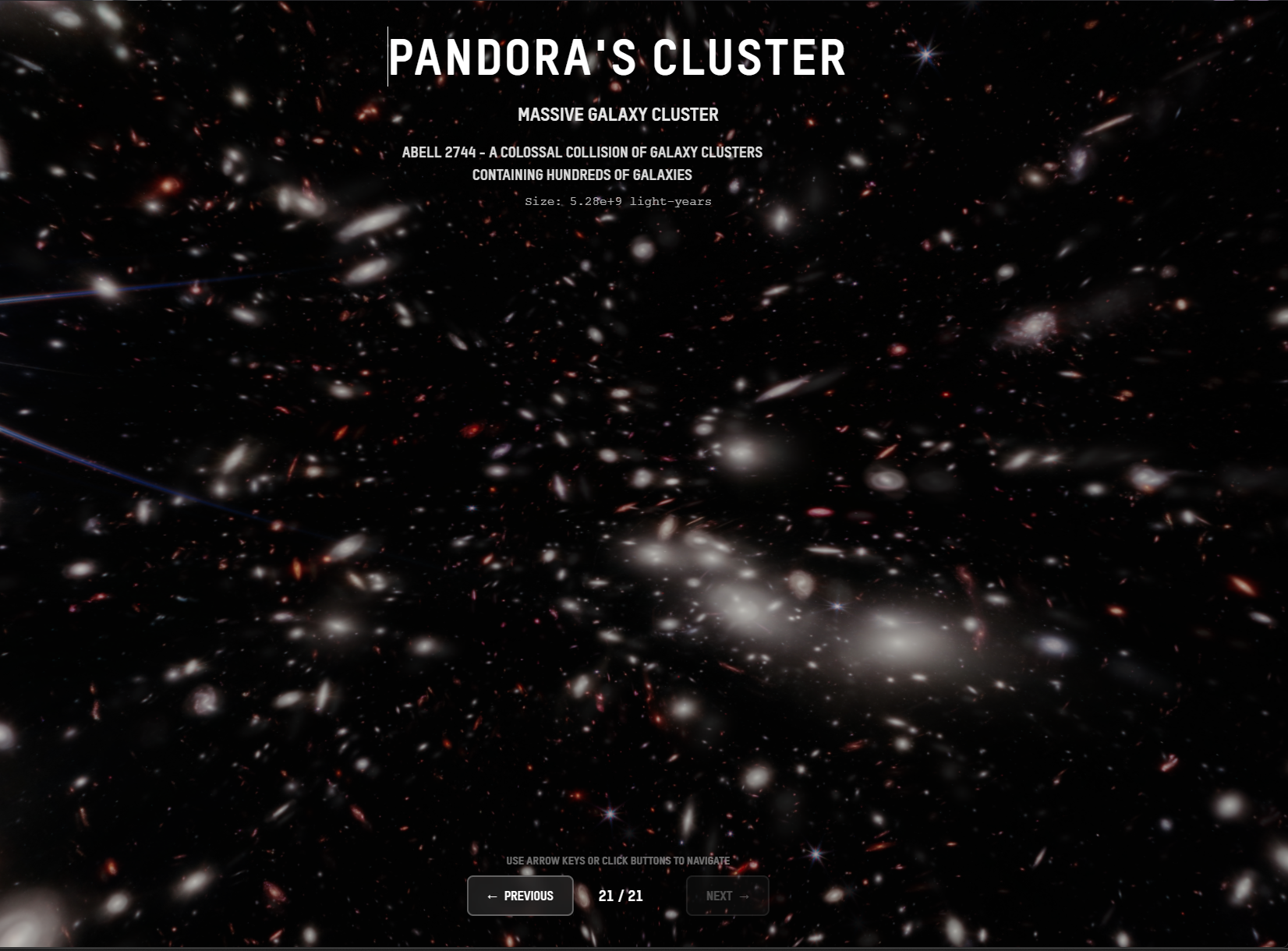

- Cosmic Structures - The Cosmic Microwave Background and Pandora's Cluster

Each transition triggers a hyperspace star effect, and the whole experience is accompanied by Hans Zimmer's Interstellar soundtrack (because of course it is). You can orbit around objects, toggle bloom effects, and jump directly to any object via the menu.

The Scale Problem

This is the core technical challenge. You can't just set object.scale = actualSizeInMeters because:

- JavaScript's floating-point precision falls apart at extreme values

- WebGL has depth buffer limitations

- Even if the math worked, the camera would need to travel astronomical distances

The solution is logarithmic normalization. Instead of working with raw sizes, I map everything to a normalized 0-1 range using log base 10:

// Map objects from Moon (3.5M m) to Observable Universe (8.8e26 m)

const minSize = 3474000; // Moon

const maxSize = 880000000000000000000000000; // Observable Universe

const logSize = Math.log10(currentObject.size);

const logMin = Math.log10(minSize);

const logMax = Math.log10(maxSize);

const normalizedLog = (logSize - logMin) / (logMax - logMin);This transforms our impossible range into something manageable. The Moon maps to 0, the Observable Universe maps to 1, and everything else falls proportionally in between.

Camera Positioning by Scale

Different object types need different viewing distances. You want to see planets up close, but galaxies need more room to breathe. I split the normalized range into four zones:

// Camera distance based on scale category

if (normalizedLog < 0.25) {

// Planets: camera at 100-150 units

targetCameraZ = 100 + normalizedLog * 200;

} else if (normalizedLog < 0.5) {

// Stars: camera at 150-300 units

targetCameraZ = 150 + (normalizedLog - 0.25) * 600;

} else if (normalizedLog < 0.75) {

// Galaxies: camera at 500-1000 units

targetCameraZ = 500 + (normalizedLog - 0.5) * 2000;

} else {

// Cosmic structures: camera at 1000-7400 units

targetCameraZ = 1000 + (normalizedLog - 0.75) * 4000;

}The actual 3D scene uses consistent units (roughly 1-100 range), but the visual perception of scale is preserved through camera distance and transition timing.

The Objects

Here's what we're working with:

| Object | Actual Size | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Moon | 3,474 km | Natural Satellite |

| Earth | 12,742 km | Planet |

| Jupiter | 139,820 km | Gas Giant |

| Sun | 1.39 million km | G-Type Star |

| Betelgeuse | 1.2 billion km | Red Supergiant |

| Stephenson 2-18 | 2.8 billion km | Largest Known Star |

| Milky Way | 100,000 light-years | Barred Spiral Galaxy |

| Observable Universe | 93 billion light-years | Everything |

That's a 10^23 range. The Moon could fit inside the Observable Universe about 253,000,000,000,000,000,000 times.

The Tech Stack

React Three Fiber provides a declarative React wrapper around Three.js. Instead of imperative WebGL calls, I can write components like <mesh> and <sphereGeometry> that integrate with React's component model.

Three.js handles the actual 3D rendering. Textured spheres for planets, emissive materials for stars, and point particles for star fields.

@react-three/postprocessing adds the bloom effect that makes stars glow. This is optional and toggleable since it's expensive on mobile devices.

TypeScript throughout for type safety, especially important when passing scale values between components.

Rendering Different Object Types

Not all celestial objects are created equal. A planet is fundamentally different from a star, which is different from a galaxy. Each type needs its own rendering approach.

Planets: Textured Spheres

Planets are the simplest - just textured spheres with slow rotation:

function PlanetRenderer({ object, currentScale, currentOpacity }) {

const meshRef = useRef<THREE.Mesh>(null);

const texture = useLoader(TextureLoader, object.texture);

useFrame(() => {

if (meshRef.current) {

meshRef.current.scale.setScalar(currentScale.current);

meshRef.current.rotation.y += 0.002; // Slow rotation

}

});

return (

<mesh ref={meshRef}>

<sphereGeometry args={[1, 64, 64]} />

<meshStandardMaterial

map={texture}

roughness={0.7}

metalness={0.1}

transparent

/>

</mesh>

);

}Stars: Emissive Glow + Point Light

Stars need to actually glow. I use Three.js emissive materials plus an outer glow sphere rendered on the back side:

function StarRenderer({ object, currentScale, currentOpacity }) {

return (

<group>

{/* Main star sphere with emissive material */}

<mesh ref={meshRef}>

<sphereGeometry args={[1, 64, 64]} />

<meshStandardMaterial

color={object.color}

emissive={object.color}

emissiveIntensity={1.5}

/>

</mesh>

{/* Outer glow - rendered on BackSide for halo effect */}

<mesh ref={glowRef}>

<sphereGeometry args={[1, 32, 32]} />

<meshBasicMaterial

color={object.color}

transparent

opacity={0.3}

side={THREE.BackSide}

/>

</mesh>

{/* Point light for scene illumination */}

<pointLight

color={object.color}

intensity={currentOpacity.current * 2}

distance={50}

/>

</group>

);

}The BackSide trick renders the inner surface of the glow sphere, creating a soft halo around the star without z-fighting issues.

Galaxies: Billboard Sprites

Real galaxies have hundreds of billions of stars. Rendering even a fraction of that would melt your GPU. Instead, I use billboard sprites - flat planes that always face the camera:

useFrame(({ camera }) => {

// Billboard effect: always face the camera

if (meshRef.current) {

meshRef.current.quaternion.copy(camera.quaternion);

}

});This is a classic game dev trick. From any viewing angle, the galaxy texture looks correct because it's always perpendicular to your view direction.

The Hyperspace Effect

When you travel between objects, I wanted that classic sci-fi "stars stretching past you" effect. The implementation is surprisingly simple: 2000 particles that move based on camera velocity.

function HyperspaceStars({ count = 2000, velocity = 0 }) {

const pointsRef = useRef();

useFrame(() => {

const positions = pointsRef.current.geometry.attributes.position.array;

// DRAMATIC amplification - velocity * 800 creates the streak effect

const speed = velocity * 800;

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

// Move stars toward camera (negative Z)

positions[i * 3 + 2] -= speed * particles.speeds[i];

// Recycle stars that pass the camera

if (positions[i * 3 + 2] < -250) {

positions[i * 3 + 2] = 250;

// Randomize X/Y for variety

positions[i * 3] = (Math.random() - 0.5) * 500;

positions[i * 3 + 1] = (Math.random() - 0.5) * 500;

}

}

pointsRef.current.geometry.attributes.position.needsUpdate = true;

});

// ... render code

}The key insight is particle recycling. Instead of creating/destroying particles, I just teleport them back to the far plane when they pass the camera. This keeps the particle count fixed at 2000 regardless of how long you travel.

The velocity * 800 multiplier is intentionally extreme. The raw velocity from camera lerping is tiny, so I amplify it dramatically to get that hyperspace streak effect.

Smooth Transitions

Jumping instantly between a planet and a galaxy would be jarring. The transition system calculates duration based on how big the scale jump is:

const nextObject = () => {

const currentSize = spaceObjects[currentIndex].size;

const nextSize = spaceObjects[currentIndex + 1].size;

// Bigger scale jumps = longer transitions

const sizeDiff = Math.log10(nextSize) - Math.log10(currentSize);

const duration = Math.max(400, Math.min(1200, 400 + sizeDiff * 150));

setTimeout(() => {

setCurrentIndex(currentIndex + 1);

}, duration);

};Jumping from Earth to Mars (similar sizes) takes ~400ms. Jumping from the Sun to the Milky Way (massive scale difference) takes ~1200ms. The logarithm ensures the timing feels proportional to the perceived "distance" traveled.

Camera movement uses linear interpolation (lerp) for smooth animation:

useFrame(() => {

currentCameraZ.current = THREE.MathUtils.lerp(

currentCameraZ.current,

targetCameraZ.current,

0.12 // Smoothing factor

);

});Pandora's Cluster: A Special Case

Pandora's Cluster (Abell 2744) is a massive collision of galaxy clusters captured by the James Webb Space Telescope. The JWST imagery is so stunning that I wanted to showcase it without any 3D objects getting in the way.

This required special handling:

- No 3D object rendering - The scene shows only the JWST background image

- Multi-layer parallax - Multiple image layers at different depths create depth perception

- Locked camera rotation - Polar angle is constrained to keep the image properly oriented

- Adjusted bloom parameters - Lower intensity to preserve the JWST star details

// Pandora's Cluster gets different bloom settings

<Bloom

intensity={isPandorasCluster ? 0.8 : 1.5}

luminanceThreshold={isPandorasCluster ? 0.9 : 0.2}

radius={isPandorasCluster ? 0.5 : 0.8}

/>Limitations and Workarounds

No True 3D Galaxies

Galaxies are billboard sprites, not volumetric particle systems. A proper Milky Way visualization would need millions of particles with realistic distributions. I have procedural galaxy code (using logarithmic spirals and Gaussian distributions), but the performance hit wasn't worth it for this use case.

Browser Audio Policy

Modern browsers require user interaction before playing audio. The Interstellar soundtrack only starts after your first click, keypress, or scroll. I fade the volume in over 1 second to avoid jarring audio starts.

Bloom is Expensive

Post-processing bloom looks gorgeous but tanks performance on mobile devices. I made it toggleable via a settings button. The experience works fine without it - stars just don't have that cinematic glow.

No LOD System

Every object renders at full detail regardless of distance. A proper Level of Detail system would swap in simpler geometry for distant objects. This would be a good future optimization.

Device Capability Detection

For Pandora's Cluster, I detect device capabilities and load different quality textures:

// Load high-quality or mobile textures based on device

const capabilities = getDeviceCapabilities();

const sphereSegments = capabilities.isMobile ? [64, 32] : [128, 64];What I Learned

-

Logarithmic scales are essential for cosmic visualization. You simply cannot work with raw astronomical units in a real-time renderer.

-

Billboard sprites are underrated. For distant objects that you'll never see from the side, a textured plane is indistinguishable from complex 3D geometry.

-

Particle recycling beats particle spawning. Keeping a fixed pool and teleporting particles is way more performant than dynamic creation/destruction.

-

Smooth transitions matter more than instant accuracy. Users forgive a lot of visual simplification if the motion feels right.

-

Device detection enables graceful degradation. The same codebase can serve desktop and mobile with different quality settings.

Resources & Further Reading

Space & Scale:

- Powers of Ten (Eames, 1977) - The classic short film that inspired this project

- Scale of the Universe Interactive - Another interactive scale visualization

- NASA's Eyes on the Solar System - Official NASA 3D solar system explorer

Technical:

- Three.js Documentation - The 3D library powering everything

- React Three Fiber - Declarative Three.js for React

- Logarithmic Scale - The math that makes this possible

- Linear Interpolation - Smooth animation fundamentals

Space Facts:

- Observable Universe - How big is everything?

- JWST Pandora's Cluster - The image used in this project

- Stellar Classification - Why stars have different colors

- Spiral Galaxy Structure - The mathematics of galaxy arms

Try It Yourself

Navigate from the Moon to the edge of the Observable Universe. Some things to try:

- Use arrow keys for quick navigation

- Click and drag to orbit around objects

- Toggle bloom on/off to see the performance difference

- Jump directly to Pandora's Cluster to see the JWST imagery

Check out the live demo and let me know what you think!

Questions about the implementation? Hit me up on GitHub or LinkedIn.

Enjoyed this post?

I write about AWS, React, AI, and building products. Have a project in mind? Let's chat.